Morrissey

was seven when he first suspected that the world didn’t fit him quite right.

Two sizes too big or two sizes too small, he couldn’t be sure. All he knew was

that planet Earth pinched him in all the wrong places. Discovering this

uncomfortable truth wasn’t like when you learn there is no Santa Claus, or that

In The Beginning, Man created God and not the other way around. No. The truth

had hit him very much like the tight, smelly fist of a schoolyard bully called

Norman Riley.

The

fight, if you could call it that, didn’t last long; a three against one attack

rarely does. Why do thugs always travel in threes? But Morrissey managed to get

off one good shot that seemed to make his point. After that, he spent most of

the time blocking Norman’s punches with his nose while his henchmen pinned

Morrisey’s arms.

Later

that night, he sat at the dining room table, silently pushing peas around his

plate while his mum sat patiently opposite. She was too good at mothering to

force him to talk before he was ready, but he knew she couldn’t go on

pretending he didn’t have an entire tissue box bunged up his nose to stop the

bleeding.

“Do

you want to talk about it?” she said softly.

Morrissey

shrugged the question away without meeting her gaze. Finally, he answered.

“Norman Riley is a wanker.”

His

mum suppressed a grin. “Davey! You can’t call him that.”

“Well

he is. He’s a bully and a wanker.”

“But

he’s never picked on you before.” A twitch of worry flickered across her face.

“He hasn’t, has he?”

Being

the new kid in town made Morrissey easy prey in Norman’s book, having only

recently moved to London from a small town south of Sheffield. Up until now,

he’d been able to avoid the brunt of Norman’s torments; there were plenty of

other victims further down the food chain. “No. I can usually stay out of his

way.”

“But

not today?”

“Not

today.” Today, Norman had come at him with a full-on purpose. Kids can be

horrible to one another, and Norman excelled at horrible. “He said…he said

things.”

His

mum tried to defuse the situation with one of her tender smiles. “People say

things all the time, Davey. Doesn’t mean we have to start fights over them.”

Morrissey

glared. “Does it look like I started the fight?”

“No,

but — “

“It

was about you.” The words came rushing out, unbidden. “He said things about

you.”

She

stiffened. “What…sort of things?”

Morrissey

replayed the scene over in his head, complete with Norman’s malicious glee at

having spread the poison. “He said you and his mum got into an argument at the

Co-Op. Didn’t you just say that we can’t go around starting fights?” His mum

looked away, sheepishly. “He said the fight was about whether or not UFOs are

real. How is that even worth fighting about? He said you told her you’d seen

one, that you’d even seen an alien.” His mum’s fascination with

extraterrestrial phenomena was no secret to him; they’d often make a game of it

as they looked up at the stars. Sometimes, when they were out in public, they

would play a game of spot the alien, playfully pointing out likely candidates

who could be extraterrestrials amongst the passersby, making up fantastic

planets complete with complex races and civilisations. But that was a game.

Their game. Norman had turned it into something vile and twisted. “He said you

were a crackpot. A freak. A mental case.” Morrissey turned his eyes up from his

plate, fighting the well of tears. “Is it true? Did you see one — an alien?”

His words felt sour and accusatory on the way out.

His

mum blanched. Morrissey could tell she was struggling for just the right

answer. “That’s silly, Luv. Why would I say that?”

“Why

would Norman say that? He’s not smart enough to make something like that up. Is

it true?”

She

took too long to answer. “I’m so sorry, Luv, I really am. It’s something I

don’t like to talk about.”

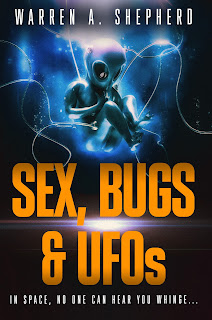

Warren A. Shepherd was seven when he first realized the world didn’t fit him quite right. Two sizes too big or two sizes too small, he couldn’t be sure. But having been transported from the streets of London, England to the streets of Toronto, Canada at such a young age left him with a profound sense of alienation — a boy with one foot in each world yet belonging in neither. The experience, however, did sharpen his sense of self-awareness and made him a keen observer of the human (and not-so-human) condition.

When he sees what humankind is capable of, both the good and the bad, he imagines how we would cope amongst the stars and is driven to tell stories of strange new worlds to try to explain the one that he often cannot.

After all, it takes an alien to know an alien…

Connect with the Author: